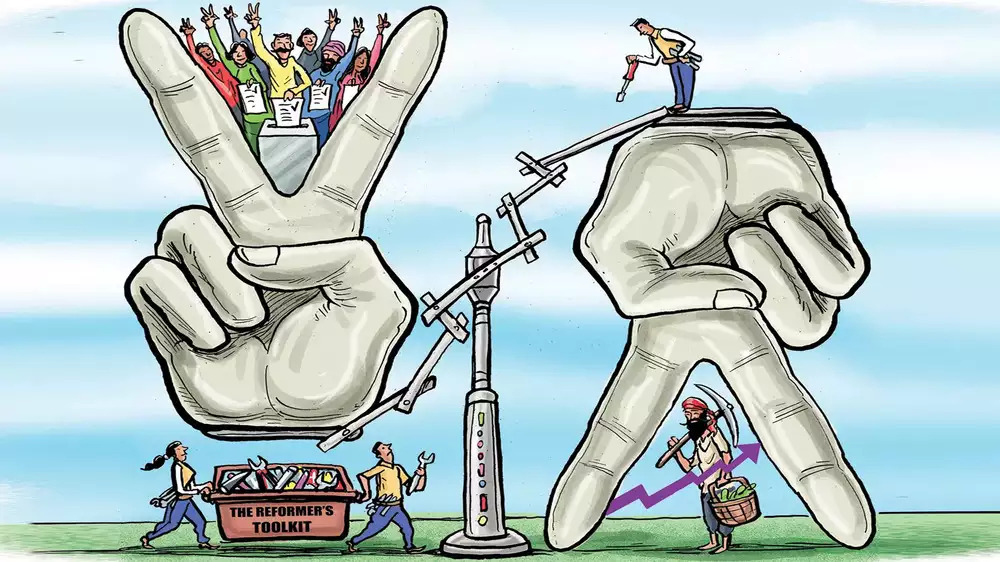

Prime minister Narendra Modi stunned the nation on November 19 when he revoked three farm laws that had led to sustained protests during the past year. A government at the zenith of power, with a strong majority, had listened to the people. It was a victory for India’s democracy. But it was a defeat for the farmer, crushing his hopes of freedom from trader cartels, state functionaries and a peasant’s life. How does one reconcile a victory for democracy with the defeat of the economy? What does this mean for the future of reforms? There are seven sobering lessons from this fiasco. Together, they form a toolkit for the future reformer.

There is an inherent mismatch between politics and economics. Politics is T20 cricket but economics is a five-day test match. A reformer seeks long term prosperity while the politician’s survival depends on the next election. Clearly, the rollback of the farm laws was influenced by elections in U.P. and Punjab. The problem, however, is that India is perennially in election mode. Hence, the first tip to the reformer is to push for simultaneous elections.

The Constitution envisaged a five year electoral cycle but state governments began to fall randomly after the 1970s, upsetting the cycle. A good compromise between the state’s ability to act and its accountability to the people would be to hold elections on two fixed dates, every five years at the centre and two and half years later in the states. If a government were to fall between those dates, the house would not be dissolved; legislators would be forced to cobble a new government or face president’s rule.

The second tip is to get the states to enact laws (not the centre) on the State or Concurrent list. When opposition to the farm laws came from the northwest, government should have encouraged other states (especially BJP states) to implement the reform. Once farmers of Punjab and Haryana would see farmers’ incomes rising in the neighbouring states, they would come around. This is what happened with the VAT tax in 2005. When some states refused to implement it, the government allowed them to move at their own pace. Within 18 months all states fell in line. Learning from GST Council’s success, the PM should employ the National Development Council of chief ministers to push the reforms.

Three, far reaching reforms need to be sold. Margaret Thatcher, the legendary reformer, used to say, “I spend 20% of my time doing the reforms and 80% selling them.” All the reformers in India have failed to convince people about the competitive market. Hence, thirty years after 1991, India still reforms by stealth. Indians still believe that reforms make the rich richer and the poor poorer, despite so much evidence to the contrary. People still cannot distinguish between being pro-market and pro-business.

Even a reform with obvious benefits needs explaining. All three farm laws were in the farmer’s interest, enhancing his freedom. The first law gave a choice to sell in or outside the mandi. The second gave freedom to stock and store produce. The third gave freedom to enter forward contracts, which passed the risk on to the buyer. Despite liberating the farmer from the clutches of middlemen, some farmers protested. Reformers make the mistake in thinking you can change the world through brute sanity. You need to be patient and build trust over time.

Four, reforms

need consent of the governed in a democracy. The process of reforming is thus as important as the content. The farm laws were introduced as ordinances, then converted to bills in parliament and passed by a brute majority without debate. They escaped the normal process of deliberation in the Standing Committee. This was a mistake. The only recourse for the farmers then was to take to the streets.

Five, reformers need to take a holistic view. The Indian farmer is poor because there are too many people working on the farm. Our only hope is large-scale expansion of low-tech manufacturing to absorb this surplus labour. The farm laws would have provided breathing time for the economy to create these jobs. If this had been explained to farmers, it would have given credibility to the reforms.

Six, reforms have losers in the short term. They often hurt a small minority while helping the large majority. If the minority is well organized, well-funded, and articulate, it can derail the reform, as it did the farm laws. The cartel of aratiyas stood to lose when the farmer got the freedom to sell outside the mandi. They funded the protests. Reformers in future need to molly-coddle, incentivise, look after the losers.

Seven, it is easier to do reforms during a crisis when people are more accepting of sacrifice and radical action. The 1991 reforms went through because the nation was bankrupt. Similarly, it was smart for the Modi government to embark on agricultural reform during the Covid crisis. Thus, the timing of the farm laws was not wrong, as many critics have alleged.

It is a sad day when democracy defeats economic sanity. After the PM’s retreat from the farm laws, many believe that reformers will be reluctant to touch agriculture for a generation. True, it’s a setback for India’s reform agenda and a probable return to the politics of freebies. However, Item 2 in the toolkit offers a ray of hope. The PM should encourage, incentivise the states to enact the farm laws in the manner of the aborted land law amendments of 2015, now adopted in 11 states. Some states have also adopted some of the farm laws. It will be a slower, messier process, but surer in the end. So, all is not lost.

Source: Times of India