On Sunday night the anchor of a TV show sneeringly and repeatedly referred to Prime Minister Narendra Modi's $5 trillion GDP target. The show was on the poor state of our cities and the well-meaning anchor didn't mean to demonise economic growth even though it came out sounding that way. When this was pointed out to her, she replied in her defence that India should grow but with responsibility to the environment. No one could disagree with that but the viewer was left unsure about the virtues of growth.

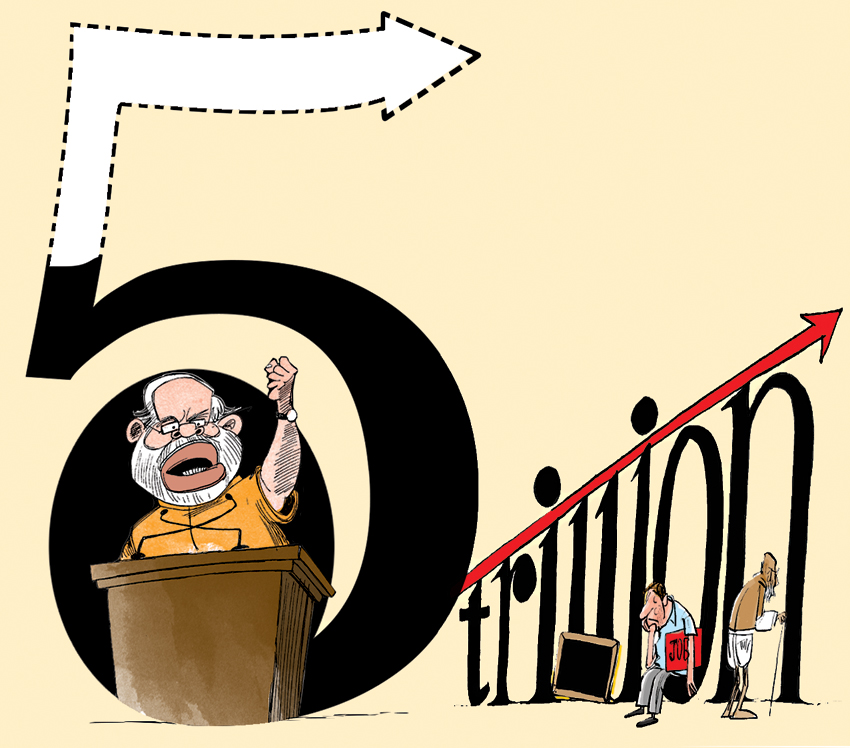

Ever since the $5 trillion goal was announced last week, it has set off a healthy debate with Modi calling his critics "professional pessimists". It is a good thing for a nation to aspire to a target. It also suggests that Modi 2.0 has a new mindset – a happy change from the "garibi hatao" mindset of giveaways that afflicted Modi 1.0 after Rahul Gandhi's jibe about a "suit-boot sarkar", which led to an unhappy race to the bottom during the recent general election. The ambitious target restores the growth mindset that got Modi elected in the first place in 2014.

The pursuit of higher GDP is easy to malign – it was invented during the industrial age and has its limitations. Many blame growth for harming the environment. They want governments to stop chasing money and start caring about the people. But it is also understandable why GDP remains the best guide for policy makers. In recent years growth has lifted more than a billion people around the world out of crushing poverty.

Only through growth does a society create jobs. Only growth provides taxes to the government to spend on education (that brings opportunity and equity) and healthcare (that improves nutrition, decreases child mortality and allows people to live longer.) In India, growth provided the means to bring subsidised gas to rural households to counter indoor air pollution from burning dung and wood for cooking. In 1990, this insidious form of pollution caused more than 8% of all deaths in the world; with growth and prosperity, this figure is down to nearly half today. Even outdoor pollution rises sharply when a poor nation begins to develop but declines as the nation prospers and has the resources to control it. It's not surprising that nations with high per capita GDP enjoy the highest ranks on the indices of human development and happiness.

It was not appropriate in her Budget speech to extoll the virtues of GDP growth, but the finance minister could have explained how achieving her bold target was crucial to creating jobs for the millions who voted for BJP. I would go further and make a new slogan for Modi 2.0, following Deng's example in China – "Not only garibi hatao, but amiri lao." This would capture the hopes and aspirations of the young. Instead of turning defensive about suit-boot, the right answer from a reformist prime minister should be, "Yes, I want every Indian to aspire to the comforts of a suit-boot lifestyle."

Success in achieving the $5 trillion target depends on implementing bold reforms and a change in other mindsets as well. Export pessimism, inherited from the 1950s, still persists and India's share in global exports remains a measly 1.7%. No country became middle class without exports. We must reverse the unfortunate protectionism that has afflicted the nation since 2014 and change our slogan to "Make in India for the World". Only through exports will come the high productivity jobs and acche din for our aspiring youth.

Second, growth and jobs will only come through private investment. Investor sentiment is weak and the biggest investors find India's environment turning hostile. The Budget has exacerbated this and it may be one reason for the stock market crash. Third, although it has become a major exporter of farm produce, India continues to treat its farmers like poor peasants. Farmers need freedom of distribution (scrap APMCs, Essential Commodities Act, etc), production (encourage contract farming), cold chains (liberalise multi-brand retail), and a stable policy on exports. Bleeding subsidies for fertilisers and PDS must be replaced by direct benefit transfers.

It is not enough to implement reforms, Modi needs to sell them. To begin with, sell them to his party, to RSS and allied saffron units. And then to the rest of the country. Margaret Thatcher used to say famously that she spent 20% of her time doing reforms and 80% selling them. The previous reformers – Narasimha Rao, Vajpayee, and Manmohan Singh – failed in this task. With his overwhelming mandate Modi should expend some of his political capital in this task. It is high time India stopped reforming by stealth.

In democracies the winner's honeymoon usually lasts a hundred days. The best answer to critics who are sceptical about the $5 trillion goal is to show tangible results during this period. For example, pull out the land and labour reform bills from the Modi 1.0 closet; improve them, and begin to "sell" these reforms in anticipation of getting them through the Rajya Sabha this time around. The FM on her part should quickly follow up on her bold disinvestment target by announcing a time bound plan for the strategic sale of other public sector companies (apart from Air India). Actions such as these will gain the peoples' trust in the ambitious $5 trillion number. And follow up with quarterly progress reports to the nation to reinforce confidence in Modi 2.0's bold vision.