November 4, 2019 was a sad day. Prime Minister Narendra Modi decided to walk out of the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) negotiations at the eleventh-hour, admitting that India couldn’t compete with Asia, especially China. It was a big and painful decision as this is no ordinary trade agreement. Had India joined, RCEP would have become the world’s largest free trade area comprising 16 countries, half the world’s population, 40% of global trade and 35% of world’s wealth in the fastest growing area of the world.

India should have joined RCEP. The deal on offer was a reasonably good one and many of our fears had been allayed. Our farmers had been given protection from imports of agricultural products and milk (say from New Zealand). A quarter of Chinese products had been excluded, and for the rest a long period of tariffs was allowed from 5 to 25 years. The deal offered a unique safeguard from a sudden surge of imports from China to India for 60 of the most sensitive products.

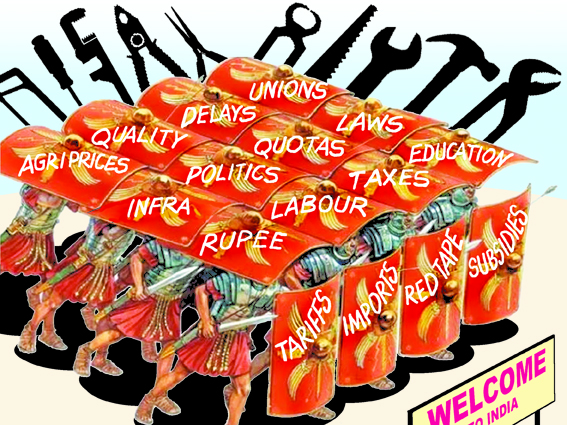

If much smaller countries in Asia – Vietnam, Thailand, the Philippines, Laos, Myanmar – can compete and have joined RCEP, why can’t India? Why does it need tariff protection, normally meant for infant industries? Why are India’s companies still infants after 72 years of Independence? No nation has become prosperous without exports; open economies have consistently outperformed closed ones. The $5 trillion target cannot be achieved without exports. The lesson from this fiasco is that India must act single-mindedly and execute bold reforms to become competitive. We can still join RCEP by March 2020. Consider this period a pause to get our house in order. It’s never too late to do the right thing. Here are ten ways to make the nation competitive.

First, get over an inferiority complex and change our old mindset of export pessimism that has limited our share of world exports to 1.7%. Pessimists fear a growing trade deficit. They forget that low cost, high quality imports are necessary to join global supply chains. Competition from imports is a school in which entrepreneurs learn to hone their skills. Ditch the bad idea of import substitution that has made a recent comeback. ‘Make in India’ should be ‘Make in India for the World’. To the voices moaning about bleak global trade prospects: Vietnam’s exports have grown 300% from 2013 to 2018 while India’s have remained stagnant. India’s share of world trade is so small – growing it will bring acche din.

Second, lower our tariffs, which are amongst the highest in the world, and have worsened in recent years through nine rounds of tariff increases in the past three years. Smart countries have a sunset clause to every tariff. Cheaper inputs from abroad will not only make our entrepreneurs more competitive but will also improve domestic productivity.

Third, national competitiveness requires collaboration across a dozen ministries and the states. It cannot be left to the ill-equipped commerce ministry. It needs a high-powered initiative under a senior Cabinet minister. Like the US trade representative, the minister should be empowered to monitor and implement reforms across ministries to enhance competitiveness. No one listens to the commerce ministry.

Fourth, a key roadblock is red tape. Keep a relentless focus on improving the ease of doing business where the country has been rewarded with significant gains in recent years. Minimise the interface of officials and citizens by transferring all paperwork online. Reduce the time it takes to enforce contracts in particular, where India’s performance is amongst the worst in the world.

Fifth, let the overvalued rupee slide, say to 80 to a dollar, which will mitigate the many cost penalties that our exporters pay. Exchange rate should not be a badge of national honour but reflect sound economic sense and competitiveness. Meanwhile, keep lowering interest rates, bringing them closer to our competitors’ levels.

Sixth, reform our rigid labour laws that protect jobs not workers. Companies have to survive in a downturn. When orders decline, you either cut workers or go bankrupt. Successful nations allow employers to ‘hire and fire’ but protect the laid off with a safety net. India should have a labour welfare fund (with contribution from employers and government) to finance transitory unemployment and re-training. We should not insist on lifetime jobs.

Seventh, acquiring an acre of land for industry is not only lengthy but also expensive. The present law, enacted during UPA-2, requires hundreds of signatures. This bureaucratic nightmare needs to be replaced by a sensible law that was, in fact, introduced during Modi 1.0 but failed to pass the Rajya Sabha. Since Modi 2.0 has better numbers, it needs to be moved urgently.

Eighth, treat farmers as business persons, not peasants. Have a predictable export-import regime for farm products – stop the present ‘switch on, switch off’ policy which harms both farmers and foreign customers. Ninth, Indian entrepreneurs bear a huge penalty versus our competitors in the cost of electricity, freight and logistics. Stop subsidising railway passengers through freight; stop subsidising electricity to farmers through industry; and bring down taxes on aviation fuel that make air cargo rates highest in the world. Tenth, keep reforming our dreadful educational system, focussing on outcomes not inputs to produce employable graduates.

There is nothing new about these ten ways to make India competitive. Fortunately, India is in the midst of an economic crisis. A crisis brings urgency to reform as the government has shown by dramatically lowering corporate tax to competitive levels. Now is the time to act. And always remember that rule-based trade and open markets are the best way to lift India’s living standards and build shared prosperity.