An exploration of desire establishes that Kama is at the very root of being human

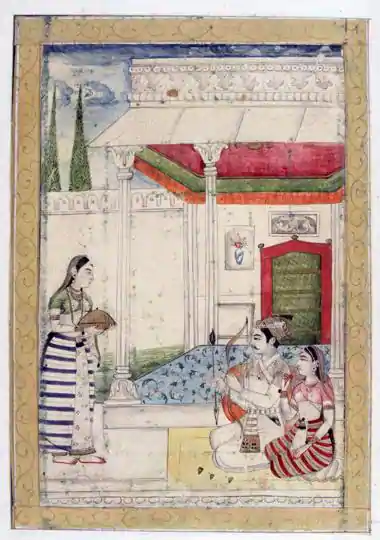

Kama or desire has a compelling quality that preys on human vulnerability often at the cost of the other three goals of life ordained in the scriptures, Dharma, Artha and Moksha. Overt emphasis on these three goals may have devalued kama to the extent that its immense creative force has been left unexplored by most. In reality, middle-class morality has placed kama solely within the sensuousness of a human body, limiting it to the idea of romantic passion that fulfils one's capability for (sexual) pleasure alone. If it is indeed as deplorable as it is made out to be why do philosophical treatises and ancient texts feature it as one of the four goals of life?

With an astute mind and a keen romantic eye, Gurcharan Das pieces together the riddle of desire to restore some balance as kama continues to oscillate between what he calls kama optimists and kama pessimists. While the optimists seek to draw a meaningful purpose of life from it, the pessimists consider it a human limitation. Simply put, kama's creative and destructive powers are manifested within the confines of pleasure seeking. Not only a force of nature, kama is a product of culture and history reflected in myriad human emotions ranging from love, affection, compassion and joy to adultery, betrayal, jealousy and violence. The challenge lies in striking a balance between these extremes.

Unlike poets and philosophers who are usually pessimistic about kama, protagonist Amar meanders from the socialist to the liberal era without denying kama a place in his life. He nurtures it as an investment to transcend human limitations. From a childhood crush to an obsession in middle age, with family life and two daughters in between, he is hit by kama's mythical five arrows during various stages of life only to learn that love is a process that develops and changes with time. The fundamental loneliness of the human condition gets the better of societal moral constraints as Amar sees that attachments beyond those permitted by society are anything but an infringement on human freedom. Can desire be allowed to remain hostage to the norms set by society and religion?

Told as a fictional memoir, the book is an ambitious undertaking on balancing the dichotomy of kama's existence in the body and its reflection in the mind and its role in drawing the individual towards finding the true meaning of life. Subject to how the reader perceives the narrative, kama is a story of physical desire seen through the percepts of the mind. It views desire, as espoused in the Rig Veda, as the first seed in the mind. It is the unique chemistry between the profane and the sacred, marked by a journey that begins with romantic love and culminates in primal energy. Kama is at the very root of being human.

It is through this story of predictable characters that Das weaves his study of desire which helps the reader understand its contemporary relevance. For all the purusharthas, the goals of life, the task is to repossess the creative life force of kama to restore harmony in the chaos of modern experience. It is time to think beyond the narrow confines of kama as a subject of sexual desire. The essence of the Kamasutra, as a metaphor, needs to be reinterpreted to free it from the gratuitous sense of guilt, thereby helping people gain relief from the stresses of life. Were the principles of the Kamasutra part of the contemporary way of life, the world would have been different indeed.

This book could not have come at a better time even as different meanings are being ascribed to human sexuality and relationships. Marriage, monogamy, adultery and, vengeance will perhaps have different connotations in the future. To make it easy to comprehend the impending irresistible transformation, Das invokes Proust: 'What matters in life is not whom or what one loves… it is the fact of loving'. As the book sketches the subtle landscape of desire, it reminds the reader of the individual's duty to fulfill his or her own capability for pleasure and to live a full life.

Das deserves praise for tracing the history of kama and its multiple strands across the history, cultures and philosophies of both the East and the West and creating a mosaic of meanings and interpretations while addressing the riddle of desire. What must not be forgotten is, as Tolstoy remarked, '...the evidence of other people is no good, all of us must have personal experience of all the nonsense of life in order to get back to life itself'.

Interview Published at Hindustan Times